By Jan Bedell, Ph.D., Master NeuroDevelopmentalist & SPED Homeschool Board Member

Teaching methods have come and gone, been expanded, and even more defined through specific curriculum. Some are geared toward specific learning styles and, since humans are all unique, it is good to have various means to get information into young brains. What if I told you about three small ways to make a big difference in your child’s education?

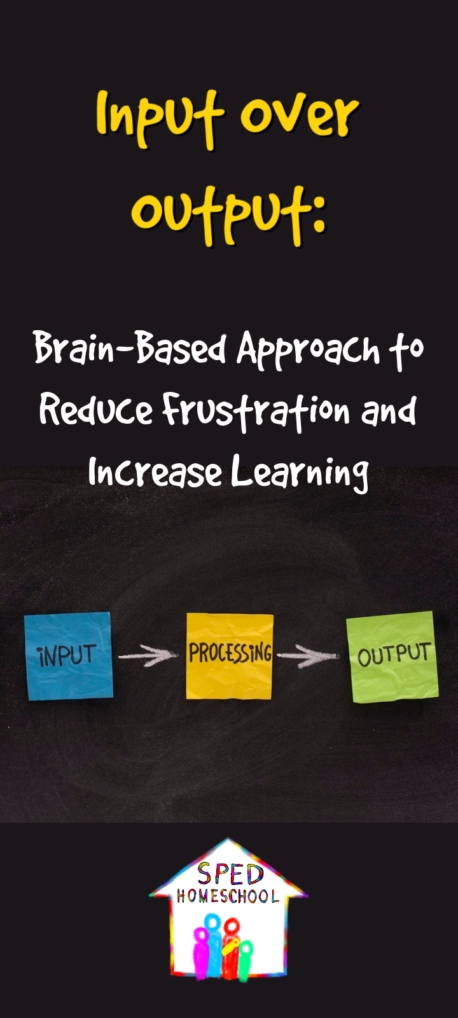

Why consider a Brain-Based Approach to learning?

Well, for starters, the realization that the brain controls everything you do would point to the importance of such an approach. If the brain is well-organized and information flows freely to all parts of the body without any sensory interference, the chances of concentrated learning go up significantly. If the individual’s short-term auditory and visual memory is humming along on all cylinders, that makes learning easier as well. If information goes into long-term memory in a way that can be easily retrieved with none of the “but you knew this yesterday” drama, the learning cycle is complete. The question is, how do we get from where we are with learning inefficiencies that make most traditional methodologies challenging for both student and teacher to that complete learning cycle outlined above? The answer lies in The NeuroDevelopmental (ND) Approach.

In a nutshell, The ND Approach focuses on using the brain’s extraordinary ability to change and grow – plasticity (find out more about Brain Plasticity at this link). By giving the brain specific stimulation or input, it responds by building brain pathways to create better overall function. The central theme of this methodology is to use the Three Keys to Input to attain better coordination, improve sensory feedback to the brain, increase short-term memory, and ensure information is stored efficiently for future use.

These Three Keys are Frequency (F), Intensity (I), and Duration (D) – FID

Frequency is the number of times the individual is exposed to the same stimulation/information. Intensity is how strong the stimulation is given. Duration is short periods of time one or more times a day and then over a period of days, weeks, or months.

What would the Three Keys look like practically in a subject area? Let’s take math computation, for instance. This is an area where we are often in a hurry for the student to be independent. Teaching is really inputting information to the students until mastery is achieved. Typically, we use techniques that are “output-based” like worksheets, speed drills, and flashcards with no answer on them. Where do we think the child will get the answer when we hold up a card with 4+5 on it? We don’t even think much about it. It is just what we do. This output method often reinforces the wrong answers and makes it even harder to master the new concept. An example of FID in math computation is when a new concept is presented, you do 3-5 problems (F) demonstrating how to do the problem. This takes very little time (D) since you are proficient in that skill. The interaction is positive, short, and pressure-free for the student (I). After the initial day or two of input in this way, it is recommended that you do 50% of the math lesson (every other problem) to keep this FID technique going.

Brain Sprints created the Rapid Recall System. This is the best Brain-Based Teaching technique where the student sees, hears, says, and writes five math facts 14 times a day (F) and it only takes 6 minutes (D). There are special sound effects to add intensity (I) to the listening sessions. Children that have had trouble remembering their math facts in the past now have them mastered.

Do you think you don’t have time to sit with your child every day for math? Let me ask you how much time do you spend checking the paper, marking, re-explaining, and dealing with frustration? Trust me, you have time if you rearrange your approach.

Three Keys to Input for Reading

Another example of FID for reading proficiency is input instead of output with phonograms. Use the phonogram cards as input cards instead of asking the student what the sound is. Pick 5 cards; hold one up at a time and say the sound; mix the order of the cards and repeat this input for 1 minute. Repeat this process twice a day for about a week. Voila! Sounds are known. If this is not the case, you have to look deeper into the brain function. The questions would be:

-

- Is there a vision challenge?

- Is information being stored in the wrong place and can’t be retrieved easily?

- Does short-term memory need to be improved?

- Is the brain disorganized?

Once the child knows all the sounds, if there are issues with using phonics, like holding all the phonograms together to be able to decode a word easily, you will want to check on the auditory processing (short-term memory). Good auditory processing is the essential prerequisite to being able to read with a phonics approach. This topic is too lengthy to enter into here, but you can learn more about this important skill with this short video: Auditory Processing

An individual’s sensory system is an important part of being able to pay attention and not be distracted or in some cases completely overloaded with hypersensitivities. If your child is not receiving sensory information well, you can get facts about the impact and some solutions from these videos from Brain Coach Tips on YouTube. It Is Not That Loud! (Hyper auditory); It’s Just a Sock (tactile oversensitivity)

The Brain-Based Teaching known as Brain Sprints NeuroDevelopmental Approach has proven effective with children with all types of labels – Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, Dyscalculia, ADHD, Autism, Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, Down, Sensory Integration Disorder. You understand more when you realize that the brain controls everything you do and when there are glitches, it just makes sense to get to the root of the issue in the brain. If you would like some guidance about where to start using a Brain-Based Approach, schedule your Free Consultation or visit www.BrainSprints.com for more information.